A US and Israeli Psychotherapist Dialogue on Anarchism in Mental Health & the War on Gaza Part I

***This is a transcript of an interview that turned into dialogue on February 23rd, 2025, between mental health workers Jeff Jones (from the US) and Itay Kander (from Israel). It has been slightly edited for clarity and length, but most of the original dialogue was kept in.

Jeff Jones:

Hello and welcome! The reason I'm reaching out to you is to show international solidarity. I feel as if we find ourselves in a really different place in the world, politically.

Now I'm not suggesting it's completely new. I'm just saying we're in a state of very advanced authoritarianism. My question is what can we do (as mental health workers currently working) in our field, if anything?

Itay Kander:

I’ve thought about these things a lot. I've been an activist in the mental health field here in Israel for quite a while now, and so I've accumulated some insight about a lot of things that are connected to that question.

Jeff Jones:

Great. I want this to be about your experiences and your thoughts. Briefly though, I’d like to explain my background.

I’ve been an activist my whole life and an anarchist as well. I helped start a therapy clinic in Minneapolis. We are a 100% collectively owned workers co-op. I don't know if there's anything similar in Israel, but really, there's only a few others in all of North America and Europe. That I know of anyways. We practice direct democracy. We work within a social justice framework. I know that this can mean different things for different people.

Here in Minneapolis in 2020 there were the riots over the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police. We were in the thick of it. And so in moments of immense suffering the question becomes: what is our role as mental health workers in this (societal suffering)?

Is it just to help alleviate anxiety and not the causes of that anxiety?

You know, here's a pill and get used to it kind of thing? Or are we meant to do more than that? I know I for one need more collective insight on these things.

And so, with that, welcome. Do you want to explain a little bit about who you are and some of your background?

Itay Kander:

Yeah, sure.

I'm a social worker. I have, what is it called in English? A second degree in public policy.

I studied that right before I realized I'm an anarchist. I used to identify simply as a socialist.

The more I read and the more active I was in all sorts of circles, I realized, actually, I’m an anarchist. Then I decided, yeah, I don't want to work in the administration here in Israel. I was and still am, to a large degree, a part of the whole alternative to psychiatric hospitalization here in Israel. I was also part of the group that tried and succeeded in creating a Soteria house here in Israel. Kind of another version of what Professor Loren Mosher did in California. I also started Open Dialog Israel, which I started with a bunch of other people more than 10 years ago in 2013. It didn't really work out for a couple of years, and then I restarted the whole project.

Jeff Jones:

May I ask what that was, Open Dialog Israel?

Itay Kander:

Open Dialog is an approach. It's a dialogical, collaborative approach. It has a lot to do with dialogic philosophy. Bakhtin or Martin Buber have a lot to do with the work, Arlene Anderson from the States and a bunch of other people. It's basically a network kind of therapy where things are extremely open and extremely collaborative. It had an immense influence on me and so I tried over the years to bring it to Israel. Then did so successfully over a bunch of years, seven years ago now. They're more than a hundred therapists working on this approach in Israel. I mean, things have really changed a lot.

I'm also a writer. I write articles about a lot of issues concerning mental health stigma. I write a lot about psychosis. So there's a lot of recurring themes in my work.

Jeff Jones:

Where can people find that work?

Itay Kander:

Well, it's mostly in Hebrew. So unless you read Hebrew, that's a bit hard to read, but I wrote one article in English. It's about mental health and anarchism. It's probably where you found me. I asked you before, but basically, that's my only serious work I translated to English. It takes time and effort to translate it to English. I've been thinking over the years of translating my work into English because I've written a lot.

But I'm kind of a local person. I mean, I'm very much connected to this culture, to these people, you know, I'm here. Not really a globalist, I guess. I’m an Israeli anarchist, even if that's a sort of a contradiction, for me, it's really not.

Jeff Jones:

No, it’s not.

What do you see as the role of anarchism in mental health?

Itay Kander:

I think a lot of types of therapy and a lot of types of therapeutic institutes are very authoritarian and have a very authoritarian mindset. I have written over the years about psychiatric hospitals and that's the pinnacle of an authoritarian institute.

Everything is decided for you there. You have barely any say about what happens to you. I think anarchism brings the idea that striving towards freedom is what makes us great. I mean real freedom, true freedom is what makes us truly great human beings. And so over the years I've thought about how we can infuse or practice with this idea that we want to give the maximum amount of freedom to people. Even for people who are in so-called “psychosis” or just have a very extreme, strange idea of what exercise in freedom really is. I really believe that giving that type of freedom in the end is what can prevent a lot of social illnesses and all sorts of suffering.

Jeff Jones:

I fully understand that because I've worked in a hospital, more in the medical detox unit, but it was psychiatric. I constantly was up against what I would say are “moral injuries” that kept happening to me. For example, people would come into detox but if they were angry or upset and would fight against the psychiatrist the reaction is “okay, now we're going to do a petition for you to go to the courts to force you into treatments.” But it was completely based upon whether that psychiatrist did or didn't like that person.

People come into hospitals when they're, typically, in crisis. And I'm sorry that they don't act obedient towards you.

Itay Kander:

Right. Why should a person just because he's in a crisis or she is in a crisis or they are in a crisis? Why should they submit to you? It really makes no sense.

Just after the great tragedy of the setup of October here in Israel there were a lot of different things happening, but one of them was that suddenly there was a tremendous need for psychological help. I wrote this article saying that the kind of institutes that we have today, because they're so based on an authoritarian mindset, what they usually do is expand and multiply the need for help.You know, somebody comes, he's in a crisis but he doesn't feel like the institute is right for him. Then he fights with the people in the institute, through this fight, more suffering is produced and then he's in a bigger crisis. Things get more and more out of hand. Then there's forced hospitalization and forced care and all of these things. The more that happens, the more people forget the true intention that they had when they came asking for help. They become so caught up in: what am I as a patient? How do I obey? When do I participate? How does my point of view collide or not collide? Where does it merge or where doesn't it merge with the perspective of the therapists?

It becomes such a messy tragic thing and what I wrote in that article is that when we have these institutes helping such a huge lot of people, we absolutely need some kind of assistance. This system cannot handle this flood. It’s so dysfunctional and It's broken. It can't help all of these people and what we need is a complete 180 degree turn, something that is completely the opposite.

Jeff Jones:

I'm thinking about how patients come in and they're supposed to perform as the “perfect patient” when there is so much going on. I don't know if this is how it's divided there, but there's a psychiatrist here, usually at the top. These psychiatrists tend to come from class privilege, typically to get through all that schooling there's class privilege. As a patient you can't relate to that. But when you're in a crisis you're supposed to be able to read the room, it's just impossible.

Itay Kander:

You can even reduce it. You shouldn't reduce it in such a way, but you can reduce it to something that is just: dysfunction. It's a system that does not fulfill its purpose. It should do X and it does Y. It's wasting a whole lot of money, it's doing a lot of damage, and it shouldn't.

Jeff Jones:

I just finished up the book Decolonizing Therapy. If you haven’t heard of it yet, it's published by A.K. Press. It's really good. I agree with the author that even though the right questions are sometimes asked it hasn't left us with a lot of great answers. I find that with left therapists or left mental health workers that sometimes we run into an issue. We can name the problem, but then say we just need to get rid of it. But then what? That's why I think these conversations are needed and rich, because I know I for one don't have the answers.

I hear little quips, you know whether you're pro medication or anti. For me, I'm just pro choice with it. I'm never going to take it away from somebody who is getting something out of it. I hear the concerns “well, the only reason why you're on that is because of capitalism.” Okay? But the anxiety/depression is still happening and I'm not feeling good. I don't like the answer to have a complete abolition of it all. Especially if we don’t have a new system coming in. And I don't have the answer to a new system either.

Itay Kander:

There was the anti-psychiatry movement in the 1970s. That was a real thing that happened not really globally, but it happened in a lot of places. Definitely in the States. Definitely in Europe. There was a huge movement. There were a lot of people who were ex-patients or psychiatric survivors involved. It happened for many years and really nothing came out of that movement. Not a lot that persisted and was sustainable. In Italy, where they abolished the psychiatric hospitals, it later morphed into another kind of psychiatric care. It's definitely the lesser of two evils, right? But it's not that. That's really why I feel that dialogical approaches and collaborative approaches are the next step.

The criticism is simply not enough and that's applicable to any field. You can criticize the education system, but unless you provide an alternative. The standard has to be extremely high because you're competing against a system that has been going on for, in some cases, hundreds of years, so you need to bring something that is magnificent, and that can give you much better results.

That's actually why soteria houses and open dialogue are so exciting to me. They have proved in different ways that they can fulfill that promise. They can be something else. They can be a good alternative.

Jeff Jones:

Briefly, here in the US, as an example, Reagan in the early 80's got rid of many of the mental health hospitals using left-wing ideas of the anti-psychiatry movement. That's the rhetoric the Regan administration used anyways. As if they cared about the patients. Similarly to when the U.S. went into Afghanistan and said they were liberating the women. As if they care. Anyway, Reagan comes in and gets rid of the hospitals. The result is a booming prison population larger than almost anywhere in the world. If we keep looking for the answers within the particular systems we're living in, that's also unideal.

I'm curious if you could speak a little bit about Soteria Houses?

Itay Kander:

Yeah. First of all, you are absolutely correct. The Reagan reform was a disaster. I think it cost a lot of people's lives. It's in the tens of thousands of people who committed suicide because of that horrible reform. So unless you do things right- it's a matter of life and death really. It's a very serious issue.

I used to feel a lot of shame because I used to be an activist here in Israel for the rights of Palestinians and then I stopped doing that and I focused on the mental health feild and every time I talked with my friends, they used to tell me “No. The field you're an activist in is just as important as that because it's still a matter of life and death.” That used to calm me down a bit.

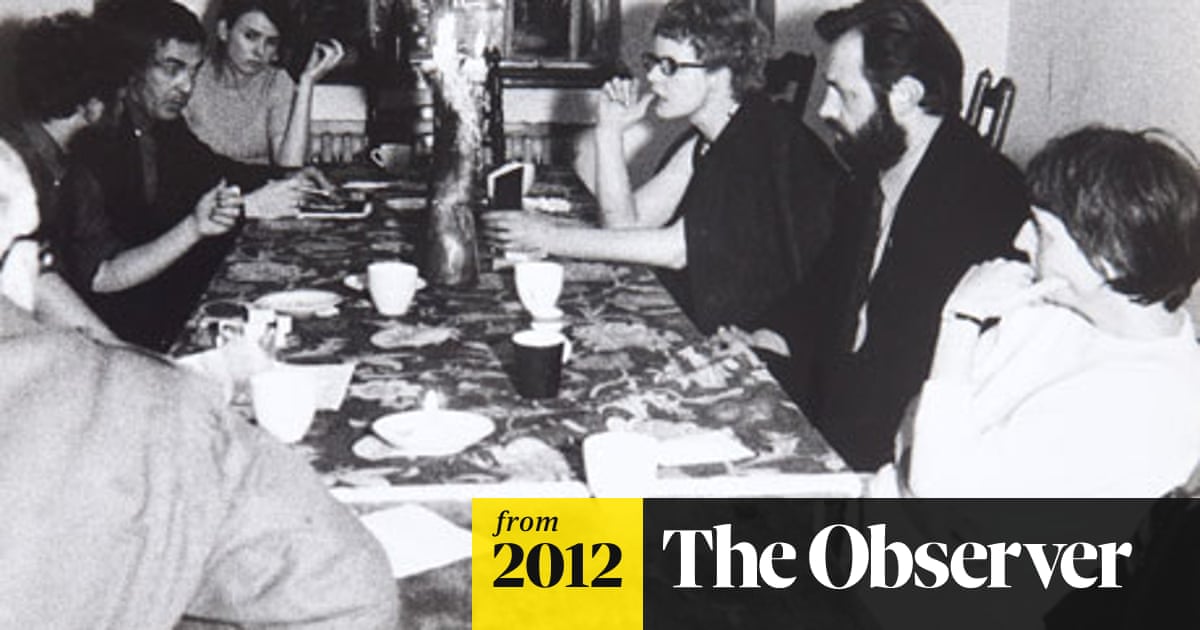

Onto soteria houses. There's a certain evolution to that concept. It started with RD Laing in the 60s/70s in the UK. He did this experiment called the Kingsley Hall. There was a house where there was no divide between the psychiatrists and the patients. Everybody lived together in the same place, but there was also a lot of drugs, psycadelic drugs, and a lot happened there. I mean, it was very “70s.” That happened for a couple of years. Then the whole project was shut down.

Actually, they changed into something else, but something far less radical. A few years later there was a researcher at the National Institute of mental health- there in the States. I hear it's an important institute.

Anyway, Lauren Mosher was the researcher. He used to be a pretty mainstream kind of guy until he heard a lot about Laing and other people. A lot of things shifted in his mind and he wanted to try out Laing’s ideas and his environment in California. He created the first soteria house. The easiest way to explain what soteria houses originally were is a place that you can go mad, can go insane in a safe environment with people who are not necessarily certified. Not psychologists, social workers, etcetera, but just good people who can take off theo pressure and be with you. The whole idea of being with you in a deeper way was very much a core idea. The place worked and this whole thing happened for a lot of years- seven or eight years.

During that time, Mosher and a bunch of other people who worked there including Voyce Hendrix also researched the outcomes of this experiment. What they saw was that it had just as good outcomes as the psychiatric hospital. With far less violence, there was barely any kind of serious violence. There's a book they wrote afterwards about the whole experience and they say- well, people smashed a bunch of plates but people usually weren’t afraid of somebody murdering someone else, there was none of that.

They were able to just go through the madness in a pretty organic way.

That experiment was a huge deal and it was very influential on a lot of people, but like I said before, that was the 70s. I think it ended in the early 80s, now barely any people are trying to recreate that experiment. Strangely enough in Israel there are currently approximately 35 soteria-like houses. Some of them deviated a lot from the original model, but some are extremely similar. Even the people who work there have studied Laing and have studied Mosher. It’s an incredible thing.

Jeff Jones:

Can you explain how they’re set up now and also what have you seen since you've been a part of it for the past few years?

Itay Kander:

I was a part of the original team who wanted to create this thing in Jerusalem, actually. We had a few years where things were very depressing for us as a group, because we couldn’t materialize our ideas. We couldn't bring them into fruition.

We we wanted to be supported by the Ministry of Health, but the Ministry of Health didn't want to do that.

In the end, it started as a private endeavor- people paid to go into the Soteria Houses.

Jeff Jones:

Is there no health insurance for mental health in Israel? I've seen a lot of places that have universal health care, but they don't usually have it for mental health.

Itay Kander:

A lot of things changed during those years in how public policy of mental health. It used to be directly under the state with state funded the psychiatric hospitals and the clinics. It's hard to explain because the health system in the United States and in Israel are very different.

If you were from the UK, I could very easily explain it to you because since the days of the British mandate, Israel has pretty much copied all of it’s medical system. There's these public insurance companies. There's four of them. During those years, approximately nine years ago, a of a lot of things in the mental health field moved and suddenly were completely funded by public insurance companies. They are funded by the state, but they have a lot of different things about them.

That is actually made the whole idea of soteria houses possible because then it wasn't the state funding the psychiatric hospitals. It was public insurance organizations. Then they had this incentive to take the money that they're getting from the government and give it to these houses. In these houses, people were there for less time than they were in the psychiatric hospitals so they saved money. Everything came together. They could save a whole lot of money and it was better for the patients.

Suddenly everything was possible.

Jeff Jones:

How are these houses set up? Are there workers or is it just mutual aid where everybody is a patient? Is there a professional say a social worker/therapist? Are there meetings? Is there group therapy? And how long do people typically stay?

Itay Kander:

Wonderful questions. There's only now starting to be good research. There has been some research in the first years, but now there's PhDs done on the material and the houses.

There are workers. Most of them are not certified therapists.

That's why they have very low wages there. It's a big, big, big problem, because they're doing the hardest work and getting the lowest payment.

There are some certified therapists there as well, just not a lot. In most houses there are psychiatrists, but they're not as dominant as psychiatrists in psychiatric wards.

There are meetings. I guess it's still too separated from the community. It's still as separated as the original Soteria Houses were from the community. It's still not there as a community center. It's not really that connected to everything around it.

These public insurance organizations only permit between one month and two months. There's barely anything that's more than that. But that's a pretty good start. For most people, going through an intense crisis it should be enough. It would be much better if they could go on being there for three, four or six months, but it's not really a place that you live in long term. It's a place to go through crisis.

Jeff Jones:

The way that I'm hearing it, and please tell me if I'm wrong. It sounds pretty revolutionary to me. Somebody is going through their crisis or that period of madness and instead of looking at the person as broken, it's more “you're not broken, we're here for you and you can do this.”

I think of almost every mental illness as “you're not broken you (just used a coping strategy) to get through something for a while”

It's just that it becomes a habit. Like social anxiety, I know for myself I had a lot of that growing up because I was extremely bullied in middle school, high school.

I would worry about it constantly “is it going to happen?”“Is it not going to happen?”

That worry is not anxiety or social anxiety. That's a real worry because it was really happening.

Then when I get out of school and I go to work, I take that same thinking pattern into my job, but people probably weren’t judging me anymore, but I still have this habitual habit. This is pretty normal for what we're going through and what I'm hearing from you is, that's what it's allowing them to do.

Instead of coming in and pumping people with medications and whatever else, you're kind of just being held as you're going through this, and telling folks you're not bad. You're not wrong. Your brain is probably working the way it should be working for what you've been going through. Whatever it is.

Maybe I'm wrong, but this is what I'm hearing.

Itay Kander:

Yeah, yeah, absolutely. There's an organization called ISPS- the International Institute for Psychological and Social Approaches to Psychosis. I was the chairperson for the Israeli chapter for a couple of years. It's a bunch of people, some researchers, some entrepreneurs, there's a bunch of people there. Some are therapists. I've learned a lot from people from ISPS.

One person specifically, stands out when I think about these things- that's John Reed, he's a researcher from the UK. He writes a lot about how almost anybody who goes through madness or psychosis has gone through some kind of traumatic event.

It doesn't just come up in someone's life. I haven't mentioned this, but I've gone through psychosis in my childhood, in my adolescence as well. Something has to happen to you. I was bullied as well. That’s part of why I was going through that hard time with myself.

What happens in the usual way we care for these people, we kind of disconnect and remove the context of whatever is happened to people and then suddenly it’s something so strange, but it's really not that strange at all.

Something that RD Laing said- he said that madness is a normal response to a mad world. It really is, and it's also something that I think open dialogue has lot to do with as well.

Jeff Jones:

Open Dialogue, sorry to interrupt, that started in Finland, right?

Itay Kander:

Yeah, it started in Finland, but it's spread out all over. There's people practicing open dialogue now in a lot of places all over the world. It really picked up in the UK. I hear there's some people doing this in the States as well, but not really a lot.In Germany, in the Netherlands, and some other places as well.

It’s still an underground movement but hopefully over the years, the more people prove it to be an efficient system and people will see the benefit.

It really started blowing up when the Finish who created open dialogue, also did long term research, and they proved that open dialogue brings really good results. It works tremendously. Less people use antipsychotic medication, there's less hospital stays etc. The greatest thing was that because they treated first episode psychosis so quickly, it didn't mature into schizophrenia. Within the DSM is needs to happen over several months and check out a few criteria. Because they treated psychosis so well, it didn't mature into schizophrenia according to the DSM, and that's just amazing.

Jeff Jones:

Like it made sense at the time, but the longer we stay in it, it becomes a habit. What you're saying makes sense to me. That first psychosis, if we stay in it, is it actually still psychosis later on or is it just habit?

Itay Kander:

Once we really listen to people, not just individuals, but people around- their family, their friends, colleagues- once we help bring true dialogue to places there's good results to that. It's not either we have good results or we're being humanistic. It's both of them. It's either we have both of them or we have neither of them. That's how I've come to support people.

Jeff Jones:

We're still trying to experiment finding the best way (forward) but there isn't one good answer for now.

Part II coming next week